Looking 'Along' and Looking 'At'

I was standing today in the dark toolshed. The sun was shining outside and through the crack at the top of the door there came a sunbeam. From where I stood that beam of light, with the specks of dust floating in it, was the most striking thing in the place. Everything else was almost pitch black. I was seeing the beam, not seeing things by it.

I was standing today in the dark toolshed. The sun was shining outside and through the crack at the top of the door there came a sunbeam. From where I stood that beam of light, with the specks of dust floating in it, was the most striking thing in the place. Everything else was almost pitch black. I was seeing the beam, not seeing things by it.Then I moved, so that the beam fell on my eyes. Instantly the whole previous picture vanished. I saw no toolshed, and (above all) no beam. Instead I saw, framed in the irregular cranny at the top of the door, green leaves moving on the branches of a tree outside and beyond that, ninety-odd million miles away, the sun. Looking along the beam, and looking at the beam are very different experiences.

But this is only a very simple example of the difference between looking at and looking along. A young man meets a girl. The whole world looks different when he sees her. Her voice reminds him of something he has been trying to remember all his life, and ten minutes' casual chat with her is more precious than all the favors that all other women in the world could grant. He is, as they say, 'in love'. Now comes a scientist and describes this young man's experience from the outside. For him it is all an affair of the young man's genes and a recognized biological stimulus. That is the difference between looking along the sexual impulse and looking at it.

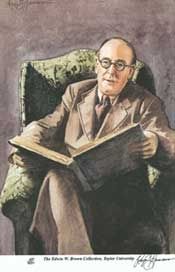

~C.S. Lewis, "Meditation in a Toolshed", 1st published in The Coventry Evening Telgraph (17 July 1945)

___________________________

Cool blog post of the day: On Narni and Narnia

Cool link of the day: Photo Gallery of Carlsbad Caverns National Park, New Mexico

garden finds himself busy from morning till night. He and I are making a path through the lower wood - first along the shore of the pond and then turning away from it up through the birch trees and rejoining at the top the ordinary track up the hill. It is very odd and delightful to be engaged on this sort of thing together: the last time we tried to make a path together was in the field at Little Lea when he was at Malvern and I was at Cherbourg. We both have a feeling that 'the wheel has come full circuit', that the period of wanderings is over, and that everything which has happened between 1914 and 1932 was an interruption: tho' not without a consciousness that it is dangerous for mere mortals to expect anything of the future with confidence. We make a very contented family together.

garden finds himself busy from morning till night. He and I are making a path through the lower wood - first along the shore of the pond and then turning away from it up through the birch trees and rejoining at the top the ordinary track up the hill. It is very odd and delightful to be engaged on this sort of thing together: the last time we tried to make a path together was in the field at Little Lea when he was at Malvern and I was at Cherbourg. We both have a feeling that 'the wheel has come full circuit', that the period of wanderings is over, and that everything which has happened between 1914 and 1932 was an interruption: tho' not without a consciousness that it is dangerous for mere mortals to expect anything of the future with confidence. We make a very contented family together. discovering that what seemed Little-Red-Riding-Hood's grandmother is really the wolf. It is better when you know it is coming: free from the shock of actual surprise you can attend better to the intrinsic surprisingness of the

discovering that what seemed Little-Red-Riding-Hood's grandmother is really the wolf. It is better when you know it is coming: free from the shock of actual surprise you can attend better to the intrinsic surprisingness of the

But it didn't matter: for all the fragments - needle-pointed desires, brisk merriments, lynx-eyed thoughts - went rolling to and fro like glittering drops and reunited themselves. It was well that both men had some knowledge of poetry. The doubling, splitting and recombining of thoughts which now went on in them would have been unendurable for one whom that art had not already instructed in the counterpoint of the mind, the mastery of doubled and trebled vision. For Ransom, whose study had been for many years in the realm of words, it was heavenly pleasure. He found himself sitting within the very heart of language, in the white-hot furnace of essential speech. All fact was broken, splashed into cataracts, caught, turned inside out, kneaded, slain, and reborn as meaning. For the lord of Meaning himself, the herald, the messenger, the slayer of Argus, was with them: the angel that spins nearest the sun. Viritrilbia, whom men call Mercury and Thoth.

But it didn't matter: for all the fragments - needle-pointed desires, brisk merriments, lynx-eyed thoughts - went rolling to and fro like glittering drops and reunited themselves. It was well that both men had some knowledge of poetry. The doubling, splitting and recombining of thoughts which now went on in them would have been unendurable for one whom that art had not already instructed in the counterpoint of the mind, the mastery of doubled and trebled vision. For Ransom, whose study had been for many years in the realm of words, it was heavenly pleasure. He found himself sitting within the very heart of language, in the white-hot furnace of essential speech. All fact was broken, splashed into cataracts, caught, turned inside out, kneaded, slain, and reborn as meaning. For the lord of Meaning himself, the herald, the messenger, the slayer of Argus, was with them: the angel that spins nearest the sun. Viritrilbia, whom men call Mercury and Thoth.

one a bit over the meanings of words (but Latin would help you almost equally for both) but it makes a confusion in one's mind about grammar and idioms--in the end one makes a horrid soup out of both. I don't know Spanish, but I know there are lovely things in Italian to read. You'll like Boiardo, Ariosto, and Tasso. By the way good easy Latin reading to keep one's Latin up with is the New Testament in Latin. Any Roman Catholic bookshop will have one: say you want a copy of the "Vulgate New Testament."

one a bit over the meanings of words (but Latin would help you almost equally for both) but it makes a confusion in one's mind about grammar and idioms--in the end one makes a horrid soup out of both. I don't know Spanish, but I know there are lovely things in Italian to read. You'll like Boiardo, Ariosto, and Tasso. By the way good easy Latin reading to keep one's Latin up with is the New Testament in Latin. Any Roman Catholic bookshop will have one: say you want a copy of the "Vulgate New Testament."

Never forget that when we are dealing with any pleasure in its healthy and normal and satisifying form, we are, in a sense, on the Enemy's ground. I know we have won many a soul through pleasure. All the same, it is His invention, not ours. He made the pleasures: all our research so far has not enabled us to produce one. All we can do is to encourage the humans to take the pleasures which our Enemy has produced, at times, or in ways, or in degrees, which He has forbidden. Hence we always try to work away from the natural condition of any pleasure to that in which it is least natural, least redolent of its Maker, and least pleasurable. An ever increasing craving for an ever diminishing pleasure is the formula. It is more certain; and it's better

Never forget that when we are dealing with any pleasure in its healthy and normal and satisifying form, we are, in a sense, on the Enemy's ground. I know we have won many a soul through pleasure. All the same, it is His invention, not ours. He made the pleasures: all our research so far has not enabled us to produce one. All we can do is to encourage the humans to take the pleasures which our Enemy has produced, at times, or in ways, or in degrees, which He has forbidden. Hence we always try to work away from the natural condition of any pleasure to that in which it is least natural, least redolent of its Maker, and least pleasurable. An ever increasing craving for an ever diminishing pleasure is the formula. It is more certain; and it's better

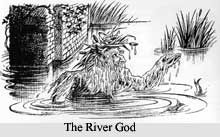

Down below that in the Great River, now at its coldest hour, the heads and shoulders of the nymphs, and the great weedy-bearded head of the river-god, rose from the water. Beyond it, in every field and wood, the alert ears of rabbits rose from their holes, the sleepy heads of birds came out from under wings, owls hooted, vixens barked, hedgehogs grunted, the trees stirred. In towns and villages mothers pressed babies close to their breasts, staring with wild eyes, dogs whimpered, and men leaped up groping for lights. Far away on the northern frontier the mountain giants peered from the dark gateways of their castles.

Down below that in the Great River, now at its coldest hour, the heads and shoulders of the nymphs, and the great weedy-bearded head of the river-god, rose from the water. Beyond it, in every field and wood, the alert ears of rabbits rose from their holes, the sleepy heads of birds came out from under wings, owls hooted, vixens barked, hedgehogs grunted, the trees stirred. In towns and villages mothers pressed babies close to their breasts, staring with wild eyes, dogs whimpered, and men leaped up groping for lights. Far away on the northern frontier the mountain giants peered from the dark gateways of their castles.  It looked first like a black mist creeping on the ground, then like the stormy waves of a black sea rising higher and higher as it came on, and then, at last, like what it was woods on the move. All the trees of the world appeared to be rushing towards Aslan. But as they drew nearer they looked less like trees; and when the whole crowd, bowing and curtsying and waving thin long arms to Aslan, were all around Lucy, she saw that it was a crowd of human shapes. Pale birch-girls were tossing their heads, willowwomen pushed back their hair from their brooding faces to gaze on Aslan, the queenly beeches stood still and adored him, shaggy oak-men, lean and melancholy elms, shockheaded hollies (dark themselves, but their wives all bright with berries) and gay rowans, all bowed and rose again, shouting, "Aslan, Aslan!" in their various husky or creaking or wave-like voices.

It looked first like a black mist creeping on the ground, then like the stormy waves of a black sea rising higher and higher as it came on, and then, at last, like what it was woods on the move. All the trees of the world appeared to be rushing towards Aslan. But as they drew nearer they looked less like trees; and when the whole crowd, bowing and curtsying and waving thin long arms to Aslan, were all around Lucy, she saw that it was a crowd of human shapes. Pale birch-girls were tossing their heads, willowwomen pushed back their hair from their brooding faces to gaze on Aslan, the queenly beeches stood still and adored him, shaggy oak-men, lean and melancholy elms, shockheaded hollies (dark themselves, but their wives all bright with berries) and gay rowans, all bowed and rose again, shouting, "Aslan, Aslan!" in their various husky or creaking or wave-like voices.

And Jane sat still till the room became filled with silence like a solid thing and there was first a scratching and then a rustling and presently she saw three plump mice working their passage across what was to them the thick undergrowth of the carpet, nosing this way and that so that if their course had been drawn it would have resembled that of a winding river, until they were so close that she could see the twinkling of their eyes and even the palpitation of their noses. In spite of what she had said she did not really care for mice in the neighbourhood of her feet and it was with an effort that she sat still. Thanks to this effort she saw mice for the first time as they really are--not as creeping things but as dainty quadrupeds, almost, when they sat up, like tiny kangaroos, with sensitive kid-gloved forepaws and transparent ears. With quick, inaudible movements they ranged to and fro till not a crumb was left on the floor. Then he blew a second time on his whistle and with a sudden whisk of tails all three of them were racing for home and in a few seconds had disappeared behind the coal box. The Director looked at her with laughter in his eyes ("It is impossible," thought Jane, "to regard him as old"). "There," he said, "a very simple adjustment. Humans want crumbs removed; mice are anxious to remove them. It ought never to have been a cause of war. "

And Jane sat still till the room became filled with silence like a solid thing and there was first a scratching and then a rustling and presently she saw three plump mice working their passage across what was to them the thick undergrowth of the carpet, nosing this way and that so that if their course had been drawn it would have resembled that of a winding river, until they were so close that she could see the twinkling of their eyes and even the palpitation of their noses. In spite of what she had said she did not really care for mice in the neighbourhood of her feet and it was with an effort that she sat still. Thanks to this effort she saw mice for the first time as they really are--not as creeping things but as dainty quadrupeds, almost, when they sat up, like tiny kangaroos, with sensitive kid-gloved forepaws and transparent ears. With quick, inaudible movements they ranged to and fro till not a crumb was left on the floor. Then he blew a second time on his whistle and with a sudden whisk of tails all three of them were racing for home and in a few seconds had disappeared behind the coal box. The Director looked at her with laughter in his eyes ("It is impossible," thought Jane, "to regard him as old"). "There," he said, "a very simple adjustment. Humans want crumbs removed; mice are anxious to remove them. It ought never to have been a cause of war. " But almost at once this identification collapsed. She was really thinking simply of hugeness. Or rather, she was not thinking of it. She was, in some strange fashion, experiencing it. Something intolerably big, something from Brobdingnag* was pressing on her, was approaching, was almost in the room. She felt herself shrinking, suffocated, emptied of all power and virtue. She darted a glance at the Director which was really a cry for help, and that glance, in some inexplicable way, revealed him as being, like herself, a very small object. The whole room was a tiny place, a mouse's hole, and it seemed to her to be tilted aslant--as though the insupportable mass and splendour of this formless hugeness in approaching, had knocked it askew. She heard the Director's voice.

But almost at once this identification collapsed. She was really thinking simply of hugeness. Or rather, she was not thinking of it. She was, in some strange fashion, experiencing it. Something intolerably big, something from Brobdingnag* was pressing on her, was approaching, was almost in the room. She felt herself shrinking, suffocated, emptied of all power and virtue. She darted a glance at the Director which was really a cry for help, and that glance, in some inexplicable way, revealed him as being, like herself, a very small object. The whole room was a tiny place, a mouse's hole, and it seemed to her to be tilted aslant--as though the insupportable mass and splendour of this formless hugeness in approaching, had knocked it askew. She heard the Director's voice.

...I am writing to help the second sort of reading. Partly, of course, because I have a historical motive. I am a man as well as a lover of poetry: being human, I am inquisitive, I want to know as well as to enjoy. But even if enjoyment alone were my aim I should still choose this way, for I should hope to be led by it to newer and fresher enjoyments, things I could never have met in my own period, modes of feeling, flavours, atmospheres, nowhere accessible but by a mental journey into the real past. I have lived nearly sixty years with myself and my own century and am not so enamoured of either as to desire no glimpse of a world beyond them.

...I am writing to help the second sort of reading. Partly, of course, because I have a historical motive. I am a man as well as a lover of poetry: being human, I am inquisitive, I want to know as well as to enjoy. But even if enjoyment alone were my aim I should still choose this way, for I should hope to be led by it to newer and fresher enjoyments, things I could never have met in my own period, modes of feeling, flavours, atmospheres, nowhere accessible but by a mental journey into the real past. I have lived nearly sixty years with myself and my own century and am not so enamoured of either as to desire no glimpse of a world beyond them.

There is the unbridgeable. To a gnome the air is

There is the unbridgeable. To a gnome the air is